In this teaching scenario, Roanna discusses the importance of an individual’s lived experience when considering care

A female with beta-thalassaemia, an inherited blood condition, talks about her experiences of managing its symptoms. Roanna also discusses the challenges she faced while in hospital and how better continuity of care could have made a positive difference.

Read Roanna’s story below and use the teaching moments and discussion points to design your teaching session.

AT-A-GLANCE

Clinical focus: Rare disease

Nursing activities: Management and ongoing care, communication, identification, education, treatment

NMC platform and outcomes: 1 (1.8, 1.9, 1.13, 1.14); 2 (2.4, 2.9, 2.10); 3 (3.2, 3.5, 3.6, 3.11, 3.12, 3.15); 4 (4.2, 4.3); 5 (5.4); 7 (7.8)

Roanna’s story

Living with beta-thalassaemia

1 I have beta–thalassaemia, which is a recessively inherited blood condition. A bittersweet thing about being born with a chronic illness like beta–thalassaemia is that I have developed some amazing coping mechanisms throughout my life. These methods have helped me deal with the daily pain I live with: headaches, joint pain, palpitations, stomach discomfort, rashes, spleen discomfort, shortness of breath and even ignoring the tinnitus I developed as a teenager from my iron chelation medication. However, when I seek medical attention, it is because of something far worse with symptoms that I can no longer manage or treat at home. As an overthinker, I go through the pros and cons of contacting or seeking medical care before I step foot into urgent care.

Severe pain: onset

2 On one particular occasion, after being an inpatient for twelve days following severe sepsis due to a central line infection (caused by ineffective infection prevention), I had a femoral line inserted on my right side as finding peripheral veins on my hands was like discovering snow in the Caribbean.

3 When the line was removed, I felt some discomfort and even though I had had six femoral lines before, this felt strange. I remember mentioning it to the senior nurse who removed the line. She assured me this was normal. It wasn’t my normal, but as I knew she had experience with removing lines, I didn’t question it further. I was excited to go home.

4 A few hours after discharge, the pain worsened, but after thinking back to the conversation I had with the senior nurse, I decided it was to be expected. I didn’t want to go back to hospital after just being released, and it was only pain so I figured it couldn’t be that difficult to treat. During the night, the pain intensified, and my mobility became affected. I began waddling like a duck. When my mother saw me, she insisted I had to be taken to the hospital. I told her that it was just pain, and they would say it’s probably nothing.

5 Fortunately for me, my mother didn’t dismiss the pain as she recognised it was beyond my normal. She insisted we visited my thalassaemia nurses who saw through my smiles and makeup and knew something was wrong. Immediately, they called the medical registrar in A&E and told them that I was in severe pain and that the cause needed to be found immediately.

Severe pain: finding the cause

6 My thalassaemia nurse took me down to A&E herself and then went on to speak to the nursing team. I was in a lot of pain which she recognised and told the team to get on top of it. The team who came to review me an hour later, commented that my specialist nurse depicted a completely different type of patient. They were unsure if I was the right patient as the thalassaemia nurse said her patient was in extreme pain, and there I was with my headphones in smiling at them and speaking coherently. I definitely couldn’t be the patient she spoke about. I assured them I was and that I was in extreme pain and needed some medication while they figured out what was happening. I told them I didn’t think I’d be able to walk to the scanners as the pain was intense. They insisted I had to walk to the scanner and that there were no porters available. I held on to my mum and waddled my way painfully to the scanner.

7 My little journey down the corridor to imaging resulted in an exacerbation of my symptoms and when I got back to my bed, I once again asked them for medication. I was advised by the nurses that they would be with me shortly and was told I needed to wait. Time passed by and I asked again when the nurses came to cannulate me. I was assured that they would get on to it as soon as I was cannulated, and blood drawn. I also mentioned to them I had a care plan in place from my haematologist, which fell on deaf ears.

Continuity of care

8 As I mentioned previously, my veins are very difficult to cannulate after 31 years of weekly blood tests, blood transfusions, intravenous iron chelation therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin. The nurses brought a green cannula (18G) with them, which I advised would be too big. They laughed and told me they understood. They said that “I had a needle phobia like everyone else (I don’t) and it doesn’t hurt any more than the rest”, that I was “wasting their time” that could be spent doing other things, that I definitely wasn’t “sick” and “should leave A&E for people who actually were”.

9 With tears in my eyes, I explained that my veins were scarred, that people were unable to get big cannulas in them and this was the reason I had central lines. I reiterated the fact that I was unwell and didn’t want to be there or waste their time either. I was then advised that they knew best as it was their job and if I wasn’t happy, I should leave. I looked at my mum in amazement and told myself to breathe – I needed to be calm as perhaps they were having a rough day. I also couldn’t walk out of A&E.

10 I gave them my hand with reluctance and after eight failed attempts with the same green cannula they brought with them (that is meant to be for single use), they walked away without any blood drawn or a cannula in situ and without saying a word. About 30 minutes later, a foundation doctor showed up saying he heard I was being difficult to cannulate. I was horrified and I explained what had happened. He saw the bruises on my hands and feet and apologised. I was close to crying at this point as despite being in pain and receiving no medication for four hours, I was being classed as “not sick”, “wasting time” and now “difficult”.

11 The doctor tried cannulating me but was also unsuccessful and proceeded to draw arterial blood. I was then reassured that the pain medication was on its way and the senior doctors were reviewing my CT scan and would soon visit me.

12 An hour passed, and two surgical doctors (a consultant and registrar) came into my room. I was asked to confirm my name and when I did, confused looks followed. The consultant had my CT scan reports in his hand and said, “the patient we expected to see would be acutely unwell and in severe pain – you don’t meet those characteristics.” I didn’t know what to say anymore after being branded by nurses for wasting NHS resources. My mum replied to them saying that I was in horrible pain but through living with thalassaemia, I have learned how to cope. I then asked what my scans showed. They paused and said, “there is a considerable amount of bleeding in your lower abdomen and perhaps a blood vessel was torn,” they then said, “but it should cause severe pain and you seem fine.”

13 After five hours of being in severe pain, I then received pain medication and was admitted for five days as it appeared that I was actually, in fact, that sick.

Final thoughts

14 Having a chronic illness is difficult and a lot of the time it is like riding the waves. It’s about trying to live as best you can despite the inconsistencies of your health.

Educator touchpoints

Teaching moments

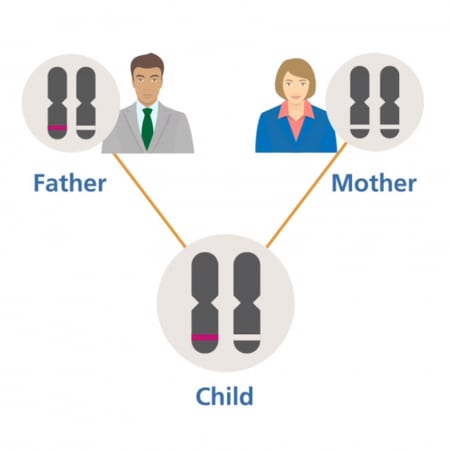

Paragraph 1 | What is beta-thalassemia and what is meant by ‘recessively inherited’?

Paragraph 5 | Explore the role of the thalassaemia nurse.

Paragraph 7 | What is a patient care plan and what would be the benefits of consulting one in this example?

Discussion points

Paragraph 3 | ‘It wasn’t my normal’. Why is this an important comment from Roanna, particularly when thinking about lived experience?

Paragraph 6 | How could the emergency nurses have handled this situation once they were briefed by her specialist nurse?

Paragraph 7 | When would it have been a good time to consult Roanna’s care plan?

Paragraph 8 and 9 | Why might the nursing staff be reacting to Roanna in this way?

Paragraph 12 | Discuss Roanna’s mother’s comment about her daughter being able to cope with and conceal signs of pain because of her condition.

Further learning

FOUNDATION KNOWLEDGE

A short animation to help explain dominant inheritance patterns

2 minutes

Learn the different ways that genetic conditions can be inherited within a family

30 minutes

EXTENDED LEARNING

Key facts about the condition, including its clinical features and genetic basis

5 minutes