Progress for paediatric gene therapy

Gene therapy for children now approved in Europe – what can this fusion of genomics and stem cell medicine mean for the future?

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recently recommended that the first commercial gene therapy product for use in children should receive market authorisation for use in the European Union – a decision hailed as a breakthrough for gene therapy.

A formidable problem: severe immune deficiency

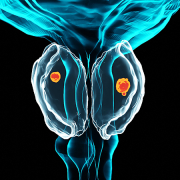

The new gene therapy, Strimvelis, is for the treatment of children with a very rare form of severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) called adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency. This is a devastating condition caused by a genetic defect in a crucial enzyme from white blood cells; without it, patients are unable to produce an effective immune response against any form of infection. Untreated, they typically die in infancy or early childhood from overwhelming infection.

Initially the only treatment was to minimise exposure, and the disease was dubbed ‘bubble boy syndrome’ after a child called David Vetter lived for twelve years in a sterile plastic bubble system. Two UK hospitals have special sterile ‘bubble units’ for children with severe forms of immune deficiency.

ADA-SCID can be cured with a successful bone marrow transplant, but the procedure is risky and relies on identification of a donor who is a close genetic match – preferably a family member. Without this, survival rates are low, and many children die before any suitable donor can be found, so providing an effective gene therapy is a major benefit.

A cure combining genetics and stem cell medicine

Strimvelis is made by insertion of a healthy adenosine deaminase gene to samples of the patient’s own immature bone marrow cells. Treated cells are then injected back into the child, where they are able to give rise to a full set of mature, healthy blood cells with effective immune function – in theory at least, throughout a normal lifespan. One of the major hurdles to effective gene therapy is achieving a long-term cure, but it is hoped that using these early stage ‘precursor’ bone marrow cells will mean just that.

Just how long the therapy will be effective remains unknown, and full details of the trial are yet to be published, but to date all patients from the clinical trial (over twenty) are alive an average of seven years after treatment – including the first patient, who was treated thirteen years ago. In terms of typical duration of therapeutic effects from gene therapy, and in survival time for these desperately vulnerable children, this is a long time.

Another advantage of this gene therapy is that using the patient’s own cells prevents the potential for graft-versus-host disease, which causes bone marrow transplants from imperfectly matched donors to fail, and means that less aggressive chemotherapy is needed as part of the treatment.

Future prospects

Gene therapy for children is likely to remain a rarity for the time being, used only in the severely ill, as it is not without risk; several children with ADA-SCID in an earlier trial developed leukaemia as a result of otherwise successful gene therapy with a similar product. However, a number of other rare diseases could potentially be treated using a similar fusion of gene therapy and stem cell medicine.

–