In this teaching scenario, Paul discusses how genetic information can help reduce the risk of developing cancer

A 62-year-old male with an inherited condition that predisposes to bowel cancer, discusses how genetic information can help reduce the risk for others like him. Paul also talks about the implications the diagnosis has had on his family and the challenge of managing the condition.

Read Paul’s story below and use the teaching moments and discussion points to design your teaching session.

AT-A-GLANCE

Clinical focus: Cancer

Nursing activities: Communication, management, family care, referral, identification, testing, return of results, treatment, ethical

NMC platform and outcomes: 1 (1.9, 1.11, 1.13, 1.18); 2 (2.5, 2.8, 2.9, 2.10); 3 (3.1, 3.2, 3.5, 3.6, 3.11, 3.12, 3.15, 3.16); 4 (4.2, 4.3); 5 (5.4); 7 (7.1, 7.8)

Paul’s story

Diagnosis

1 I have suffered from passing blood and mucus for 20 years and it was diagnosed as ulcerative colitis and it never flared up. It was just at a steady level all the while with no medication. Then after about 25 years, things changed a bit. I was referred to a consultant who said that “going to the toilet about seven times a day wasn’t a good quality of life”. I just accepted that’s what colitis meant.

2 We tried different steroids for a year which didn’t improve the condition unless I was on a very high dose, and after the year things turned worse. I was getting stomach cramps, and a further colonoscopy found there was multiple polyps in the bowel. It was suggested I had the whole of the bowel removed and a permanent ileostomy because of the threat of cancer. I had that operation in June 1999 and on the 10th day they said it was too late and I had already got cancer. It was just in passing from my surgeon that I found out there could be a genetics element, which was a long word that didn’t mean a lot. Having had the operation, we thought that it had been dealt with. Over the next 18 months, I found out that I’d got familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and learned how it could affect my family.

3 I didn’t really have any additional support from other healthcare professionals. The stoma nurse, with having a permanent stoma was brilliant. The actual operation side was great, you know. You couldn’t fault that. And the genetics side was brilliant at the clinic, but there was nothing written down. It was all told to you and you had to try and remember, and I think for my wife and myself, a lot of it just passed over us. We just thought “oh that’s interesting, it might be genetic”, but there was nothing to read to help us understand the implications to our family – we’ve got three children.

4 When I first had an appointment at the genetic clinic, one of the – they call them clinical nurse specialists now, she came out to the house and took a family history and also explained it a little bit more – not in a great amount of detail, but she was good, you know. We found she looked on us as a family, not just as a patient or something, and we felt totally at ease.

5 I saw them again 18 months later, when my FAP diagnosis was confirmed, to have a conversation about what this meant for my family, who needed to know or at least be informed so they could make their own decisions. I guess this was like genetic counselling, but we said we don’t need counselling you know. It’s not counselling as such, is it? They’re more of a friend. That’s how we found them to be. There was also a professor I saw at the genetics clinic – he didn’t look down on us and he was nice. The area was nice. The receptionist brought us a coffee and we felt at ease.

6 Having the genetic test didn’t really bother me. I had had my bowel out and the cancer was, by that time, well under control and I thought, “oh that’s it finished with me. I don’t need to worry”. I had a test for freckles behind the eye, which is an indication, and they couldn’t find any and I thought “great”. It was a week later when I had the phone call to say I had got the gene – which was a bit of a blow – because then we realised with three children, it gets a bit serious, you know. And you’d got the elation of the cancer being OK – and then suddenly they say: “Well, you know, your family could be at risk.”

7 It was only later when I look back; I think I noticed I’d been a bit irritable, a bit snappy. And not necessarily down in the dumps at all, but I think it just threw me totally out. And you were looking for ways to kind of mask it I think, as a kind of smokescreen, so you didn’t think too deeply into it. Our first thought was, with a bit of luck, none of the children will have the gene. But with three of them and it being 50/50 each time, we crossed our fingers and hoped for the best.

Identifying other family members at ‘risk’

8 I had a son who was 25 at the time and a daughter who was 28. They decided to be tested straight away but that took about six months for them to make sure that’s what they wanted to do. The genetic people were brilliant. They didn’t rush in and just chatted to them the first time. My son and daughter went back thinking they were going to have a blood test and it was another chat just to make totally sure they understood all the implications of having a genetic test.

9 When they received the results, my daughter was positive and my youngest son wasn’t. And that just floored us. You were pleased for my son and you didn’t really know how to react with my daughter. I’ve also got an older lad who didn’t want to be tested. He’s a quiet type. But it was only after my daughter’s result, and the implications of it all, that he decided to be tested. He went through the same process, and tested negative.

10 This was a hard time – how the two sons reacted with the daughter as well, and the other way round. I felt very guilty and the first thing my daughter and my wife said is: “Don’t feel guilty at all.” And I think, in the end, I perhaps didn’t feel guilty, but I still feel responsible and on a low day I still think of what’s gone on, but she has had her operation and it has prevented her having cancer. I think what did help my daughter come to terms with her result was her surgeon telling her that within two years, she would have had bowel cancer and there would have been no symptoms. So, I look on it and I think: “I’d rather me have had cancer and them find it, rather than my daughter finding out she’d got cancer.”

11 My daughter lived away from home and we didn’t see an awful lot of her. There were some other – not problems – but families move away from each other and have their own lives. And, at first, she wanted to know things about a stoma and how I had managed mine, but I suppose as she got more confidence and got a bit more information on things, then there was no need to ask about that side of it.

12 The only worrying thing I’ve found is that they tend to group all the genetic genes together and say: “this is to prevent cancer, or it might be cancerous”. But I just felt that, in the initial part, if they had just said that… They did say it was virtually 100% certain that with the gene you’d have cancer, but they never mentioned all the other little side effects of the gene, if you like. Even after the operation, I thought: “Well that’s the end of it”, but suddenly it’s: “You might have polyps in your stomach, you might have little bumps,” and things like this, and that was hard to take because you think: “Well I have had all the surgery. I’ve had all the chemo.”

Management

13 My daughter’s had the surgery but now we are having annual checks for polyps. I explain it as “the gene that lets bumps grow”, and it’s hard that I’m 62 and I read somewhere that with all the surgery, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t live until you are 60. My daughter’s 30 and you think, there’s a little bit of guilt comes in because I’m 62 now and it didn’t affect me until I was in my late 50’s, so I had had a pretty good life. Now my daughter’s 30 and starting out with all the problems and the worry of what else might be there with the gene.

14 I’m glad the genetic factor was identified. Looking back, the cancer was a minor thing. The genetics side then – although it’s got its own problems – for the future, at least we know we’re being looked after, and we’ve got the NHS to thank for that really. For instance,if they had kept the genetic side quiet then my daughter’s story could be very different. But I can understand why some people don’t want to have a genetic test or, if they do have a test, don’t want to tell anybody. You know, it’s a very private little world you get into for a while. You worry about putting stress on other family members, cousins and things like that, putting worry into them.

15 I have 13 cousins in total and they were given a number to ring should they want to be tested: there was no obligation. Two of them did ring the number, mainly for their children. I don’t fully know what’s happened, but they have started to go through it. And my sister as well, she went through the process and she’s clear. I’ve got a brother who’s 67/68 years old. He’s never had any bowel problems and his GP has made a note on his records that if he has any, then there is the possibility that it could be polyps, and he’s happy with that.

16 I think if the GPs, and some of the surgeons as well and the consultants, knew some of the basics of genetics – little bits about things – it would help. You hear people say so many times: “The GP’s never heard of it”, and you feel like you’re doing the training! The consultant who checks my stomach, he said: “You know more than I do!” And in a way you feel that: “Hold on. You should know more than me!” But I think that’s the thing – if they all know a little bit about it, and it’s mentioned around instead of talking about this op, that op, if the word ‘genetics’ crops up sometimes: I think that would be the start. And also, the information… we had to remember everything in our heads, and when you’ve got so many emotions going on, well, it’s hard to remember.

Final thoughts

17 FAP is rare, you know, but if you’ve not got something to look at, you go away from those initial meetings and think, “I’m alone”. From my own research, we found there were five families in the area with FAP. You think, crikey, it is rare, but then among those five families, there could be 30-40 people with the condition.

18 Another point is how the risk is communicated when a ‘cancer gene’ is identified. If you say to somebody that it’s 50/50 whether you get cancer, or 75%, that’s got its own problems hasn’t it – on taking the risk that you might be the lucky 25%. I think when they say 99.9% or something like that, it makes it easier in a way… but when it can affect children so young, it makes it more difficult perhaps as well. And I suppose what I am trying to say is not to treat everybody with a genetic cancer gene the same, because they do vary.

19 Lastly, I wanted to say about looking out for other family members not directly affected by the gene, like my wife. I found that the attention in the early days was all around me: “How is he? How is he doing? What’s this? He’s looking well.” They forget the partner or the immediate family, and the phone never stopped ringing. You have a major operation, and the phone doesn’t stop.

20 I would just love those who are aware of FAP and all its extra bits and pieces to get together and devise a programme of support, and offer this to the patient. I know not everyone would want to know, but I am sure many would.

Educator touchpoints

Teaching moments

Paragraph 2 | What type of test could have been used to diagnose Paul’s condition?

Paragraph 4 | How do you draw a family history?

Paragraph 5 | What is genetic counselling and why it is important?

Paragraph 6 | Remember, there is not a gene that causes FAP. It is variation in the gene that leads to the condition.

Discussion points

Paragraph 3 | Why would writing things down be clearer for Paul and his family?

Paragraph 4 | Why is taking a family history important?

Paragraph 4 | Why do you think Paul and his family liked the approach of the clinical nurse specialist?

Paragraph 6 | If Paul’s family are also at ‘risk’, what could some of the implications be? Consider the negative connotations of the word ‘risk’. What other word could you use instead?

Paragraph 8 | Why do you think Paul’s children did not rush the decision to get tested?

Paragraph 9 | How could you support Paul’s family following the positive and negative results of his children?

Paragraph 10 | How could you help Paul to manage these feelings of guilt?

Paragraph 14 | Why might some of Paul’s extended family members not want to be tested?

Paragraph 16 | Those with genetic conditions often know more than the healthcare professionals caring for them.

Paragraph 19 | What support would be needed for Paul’s family members not directly affected by the condition?

Further learning

FOUNDATION KNOWLEDGE

Tips and tools for communicating with patients about genomics

30 minutes

Learn about how a genetic family history can help to identify an inherited condition

30 minutes

Practical tips and tools to help you read, take and draw a genetic family history

15 minutes

EXTENDED LEARNING

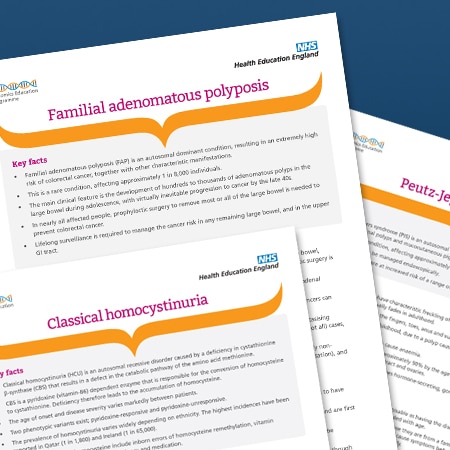

Key facts about the condition, including its clinical features and genetic basis

5 minutes