Congenital heart disease study reveals inheritance factor

Examining the genetic roots of cardiac conditions and how further research could bring benefits to patients

Most heart disease is caused by a combination of environmental and lifestyle factors, such as smoking or poor diet, interacting with genetic predisposition. The genetic variants underlying such multifactorial heart disease are thought to be common variants that are individually modest in effect. In some individuals, however, heart disease may be caused by a single genetic mutation that strongly increases risk.

The ‘faulty gene’ factor

Inherited heart disease is a fairly large group of conditions that may be responsible for abnormalities of heart rhythm, breathlessness and chest pain and sometimes sudden cardiac death. Earlier this year, stories in the media appeared about the death of Miles Frost, son of Sir David Frost, who died unexpectedly aged 31 of the inherited cardiac disorder, hyper trophic cardiomyothapy (HCM). A post-mortem on his father, who died following a heart attack in 2013, revealed they shared the same genetic condition (although this was not the cause of Sir David’s heart attack). About one in 500 people are born with the faulty gene that causes the condition; most are undiagnosed and have no symptoms. In the case of Sir David Frost, his sons had not been informed that they stood a 50% risk of inheriting this condition, for which preventative interventions are available.

Congenital heart disorders (CHD) form another large group of rare cardiac conditions. Around 1% of the population is born with a heart defect and about 10% of cases are known as ‘syndromic CHD’ – where the child shows other developmental problems such as intellectual disability or problems with other organ development. However the great majority – 90% of cases – are non-syndromic meaning that there are no other associated conditions and in milder cases the condition may even be symptomless.

For children with congenital disorders parents are often keen to know the cause. As well as just the ‘need to know’, this may also help future management of the child or to understand the prognosis. Congenital heart disease has a number of underlying aetiologies including, for example, exposures during pregnancy to drugs or infections that generally affect the developing fetus.There may also be an underlying genetic cause and identifying this in a child may mean that is possible to give advice to parents about the possibility that the conditions may happen again in future offspring.

New findings

In the past, sibling studies into CHD have generally suggested a considerable role for de novo mutations in syndromic CHD. This refers to mutations that arise spontaneously in the patient and are not seen in the patient’s parents. However, a study published in Nature this month reveals that, for some non-syndromic disorders, heritable genetic factors are at play.

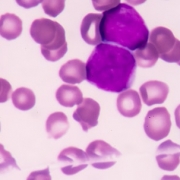

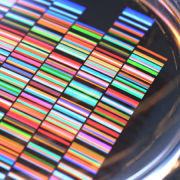

The international collaboration of researchers sequenced and analysed the exomes of almost 1,900 congenital heart disease patients and their parents. The study included both 1,891 syndromic probands (S-CHD) and 610 non-syndromic probands (NS-CHD). It confirmed that de novo mutations were an underlying factor in syndromic CHD and that non-syndromic CHD patients did not have such spontaneous mutations. However, interestingly it also showed that children with non-syndromic CHD often possessed damaging gene variants which they had inherited from their unaffected parents.

Although there have been several small studies which have hinted at this heritability, this latest research highlights the importance of large-scale studies to provide the necessary statistical evidence base. Both authors and participants of the study spoke of the imperative of sharing genomic and other health data – especially for rare diseases – to strengthen the evidence base and better inform patient and professional decision making.

–