Mainstreaming whole genome sequencing: where are we now?

Genomic testing capabilities are advancing in affordability and accessibility by the day. But what is the current trajectory of whole genome sequencing in healthcare?

As massively parallel sequencing, also known as next-generation sequencing, facilitates faster, cheaper access to the genome, genomic testing is touching more areas of healthcare than ever before. Here, we take a look at how this mission to bring genomics to mainstream healthcare has developed.

The evolution of genomic testing

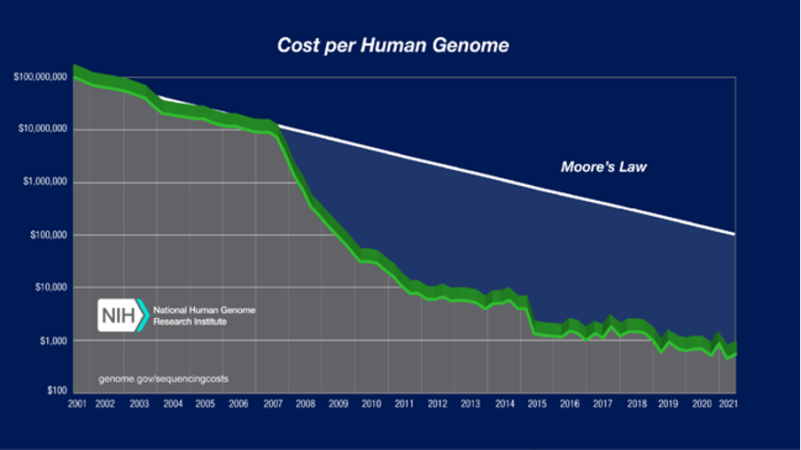

In computer science, Moore’s law predicts that computing power will double every two years, while the cost of computing technology will halve.

This means there should be a steady, linear relationship between the power of technology and its cost. Over the past 15 years, genomic technologies have completely broken this law. The graph below shows the dramatic reduction in costs of whole genome sequencing (WGS) in recent years. This graph stops at 2021, but we have seen further massive cost reductions of WGS since then. The $100 genome is on the horizon.

Figure 1: Sequencing cost per genome. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Human Genome Research Institute

The Human Genome Project was the first attempt to fully sequence the human genome. It was a worldwide effort, taking around 13 years and costing around $2.7 billion.

As governments recognised the potential of genetic technologies, technology companies began chasing ‘the $1,000 genome’ using massively parallel sequencing, which continued to reduce in cost.

Rather than testing a single gene at a time in a laborious process, massively parallel sequencing allows us to examine hundreds or thousands of genes in a single assay. Today, it is the gold standard for many tests, and sequencing the whole genome can take just one day.

Although it may not truly cost less than $1,000, and analysis of the results clearly takes more than a single day, the dramatic cost reduction and increased speed at which we can generate genomic data since the advent of massively parallel sequencing technologies has made genomic testing far more accessible for clinical use.

100,000 Genomes: a translational project

In 2012, then-prime minister David Cameron launched the 100,000 Genomes Project: an ambitious initiative to sequence 100,000 whole genomes from more than 70,000 NHS patients and families with rare disease or cancer.

Not only would the project bring the benefit of genomics to these individuals and families by attempting to find diagnoses and identify new treatment options, it would also lay the foundation and vision for the current NHS Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) by applying WGS on a large scale for the first time.

In 2018, following the 100,000 Genomes Project and to deliver on wider implementation of genomic technologies for clinical use in the UK, the NHS GMS was established.

Previously, any form of genomic testing was funded by individual UK genetic laboratories, leading to inequalities in the provision of testing across the country.

Within the GMS, laboratories can consolidate their services and now work more collaboratively across seven Genomic Laboratory Hubs (GLHs).

Establishing a national directory for genomic tests

In addition to reorganising the ways in which laboratories offer testing, the production of the National Genomic Test Directory standardised the criteria for all genomic testing in England. This document outlines the eligibility criteria for all tests that are commissioned by the NHS in England and stipulates the clinicians who can request them.

Understanding the scope of the test directory and how to use it is essential for any clinician ordering genomic tests. You can find step-by-step guidance on how to order genomic tests as part of our two-week FutureLearn course.

Mainstreaming of genomic testing

The test directory makes it clear that many genomic tests can be requested by clinicians outside of a clinical genetics setting. Now, more healthcare professionals than ever before have the responsibility of identifying and ordering tests.

This has been referred to as mainstreaming of genomic testing, and it is a key step in improving access to genomic tests and streamlining patient care.

Consequently, the roles of clinical geneticists and genetic counsellors are evolving. As well as contributing to the diagnosis of genetic disease and/or wider cascade testing in patients and families, they are increasingly providing support and advice to other clinicians, facilitating the interpretation of results and providing critical education to support the integration of genomics across the healthcare specialties.

Want to know more?

If you want to delve deeper into the GMS and its mission to change the delivery of genomics in the NHS, read this article: ‘The new genomic medicine service and implications for patients’.