Paternal age effect

Several genetic conditions have an increased chance of occurrence with increasing paternal age.

Overview

The paternal age effect is the relationship between the biological father’s age at conception of his offspring and the health effects on those offspring. There are a number of health conditions whose occurrence has been associated with this phenomenon, such as autism spectrum disorder, single-gene disorders, chromosomal conditions, pregnancy (such as miscarriage and stillbirth), neurological conditions (such as epilepsy) and mental health conditions (such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia).

Although some of the specific medical conditions associated with the paternal age effect have weak associations, overall health risks are recognised – so much so that an upper age limit (of 45 years) applies for sperm donation in the UK (though exceptions are sometimes made). In fact, sperm donors have to undertake genetic screening (for example, karyotype testing for chromosomal conditions) before eligibility is confirmed.

Why does the paternal age effect occur?

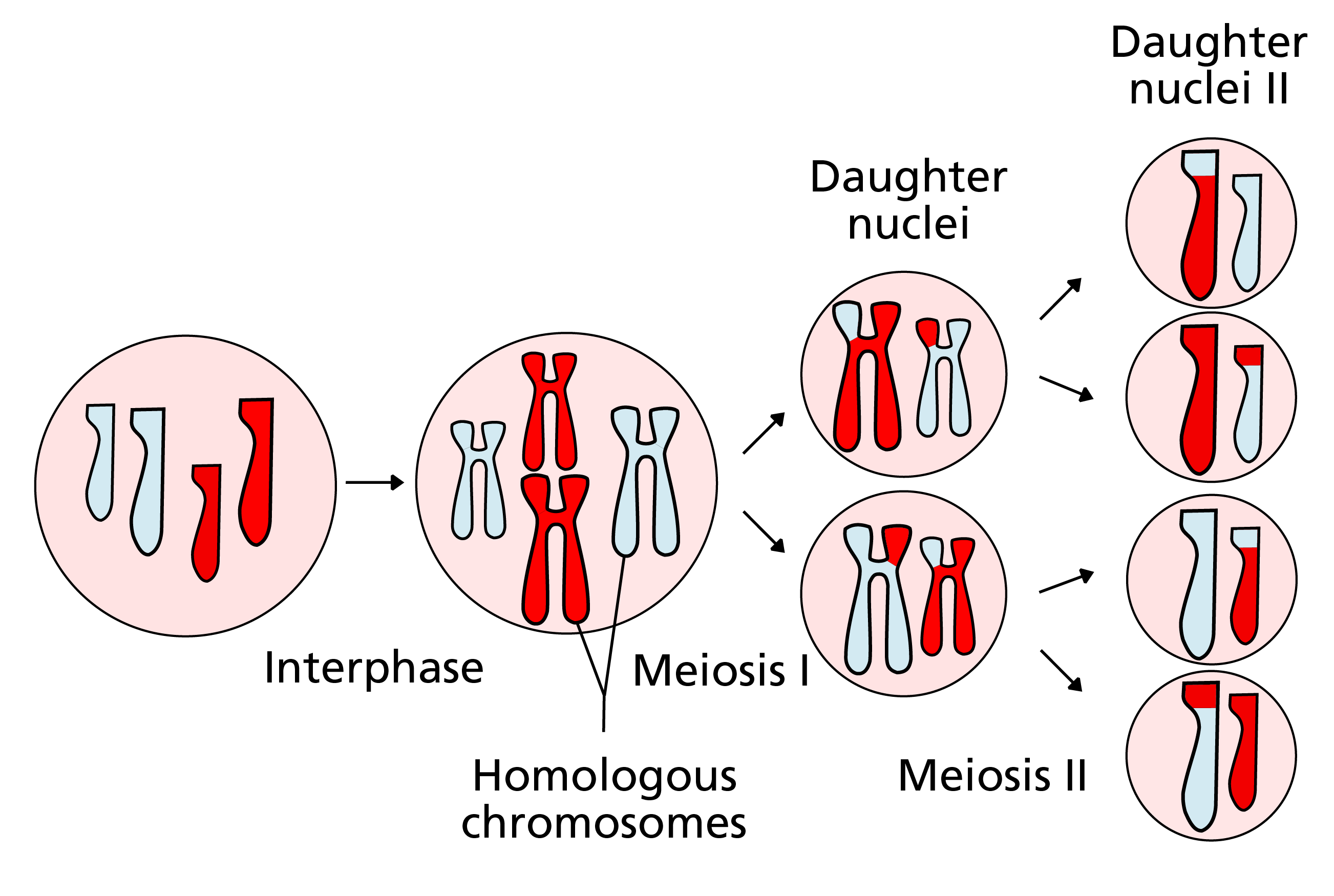

The volume and quality of sperm decreases with age. Men produce sperm on a regular basis from special stem cells called spermatogonia. The spermatogonia divide via meiosis (one cell divides into four daughter cells, each with half the number of chromosomes of the parent cell – see figure 1) roughly every 16 days after puberty. Errors occur during the copying of genetic material information, most of which are innocuous.

If an error occurs within the DNA replication phase of meiosis (prior to cell division) in spermatogonia, it can lead to an increase in the number of ‘error’ clones.

Figure 1: The process of meiosis. Diagram from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Cells with certain genetic errors have a selective advantage over other cells, and increase in number through clonal expansion. Alterations that affect the Ras/MAPK pathway (which regulates spermatogonial proliferation) in particular appear to offer a competitive advantage to spermatogonial cells, while also leading to diseases associated with paternal age.

Which genetic conditions are most affected by the paternal age effect?

Conditions caused by genes linked to the Ras/MAPK pathway (sometimes called RASopathies) often have a stronger link with the paternal age effect. Such conditions include:

- Apert and Crouzon syndrome (FGFR2);

- achondroplasia and thanatophoric dysplasia (FGFR3);

- Costello syndrome (HRAS);

- Noonan syndrome (PTPN11, SOS1, BRAF, MAP2K1, HRAS, KRAS, RAF1, SOS1 and potentially others);

- cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome (MAP2K2);

- multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (RET); and

- neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

There is also evidence (though weaker) that the paternal age effect is important in osteogenesis imperfecta.

Key messages

- There is direct correlation between paternal age and decreased sperm quality.

- Genetic abnormalities and epigenetic modifications have all been linked to older fathers.

- Disorders in the Ras/MAPK pathway are more significantly correlated with the paternal age effect.

- Autism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and paediatric leukaemia have all been linked to the father’s advanced years, as have reduced IVF success rates.

Resources

For clinicians

- Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority: Donating your sperm

References:

- Dubov T, Toledano‐Alhadef H, Bokstein F and others. ‘The effect of parental age on the presence of de novo mutations–Lessons from neurofibromatosis type I’. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 2016: volume 4, issue 4, pages 480–486. DOI: 1002/mgg3.222

- Kaltsas A, Moustakli E, Zikopoulos A and others. ‘Impact of Advanced Paternal Age on Fertility and Risks of Genetic Disorders in Offspring‘. Genes (Basel) 2023: volume 14, volume 14, issue 2, article number 486. DOI: 10.3390/genes14020486

- Maher GJ, Ralph HK, Ding Z and others. ‘Selfish mutations dysregulating RAS-MAPK signalling are pervasive in aged human testes’. Genome Research 2018: volume 28, issue 12, pages 1,779–1,790. DOI: 10.1101/gr.239186.118

- Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Scarano G and others. ‘Effect of paternal age in achondroplasia, thanatophoric dysplasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta’. American Journal of Medical Genetics 1995: volume 59, issue 2, pages 209–217. DOI: 1002/ajmg.1320590218