When to suspect a skeletal dysplasia as a cause of short stature

Short stature is often the presenting feature of skeletal dysplasia conditions, a family of heritable bone conditions.

Overview

Short stature is physiological in most cases, but it can be pathological. Some features linked with short stature may suggest an underlying causative skeletal dysplasia, such as achondroplasia.

Causes of short stature

Causes of short stature are broadly divided into two groups: physiological and pathological.

Physiological causes

Physiological causes account for 75% of cases of short stature. They include:

- delay (constitutional (germline) delay of growth and puberty); and

- familial causes.

Pathological causes

Pathological causes of short stature include:

- faltering growth (FG, accounts for around 10% of cases) – linked to chronic disease, neglect and psychological factors;

- genetic factors (account for more than 12% of cases) – including chromosomal causes and skeletal dysplasia conditions with and without underlying bone dysplasia; and

- endocrine factors (accounts for 1%–2% of cases) – such as growth hormone (GH) deficiency and receptor insensitivity.

Note that there is an overlap between all three of these pathological causes (for example, hypothyroidism is an endocrine cause that also fits within the FG category), so it is difficult to provide an exact percentage for cases caused by endocrine factors.

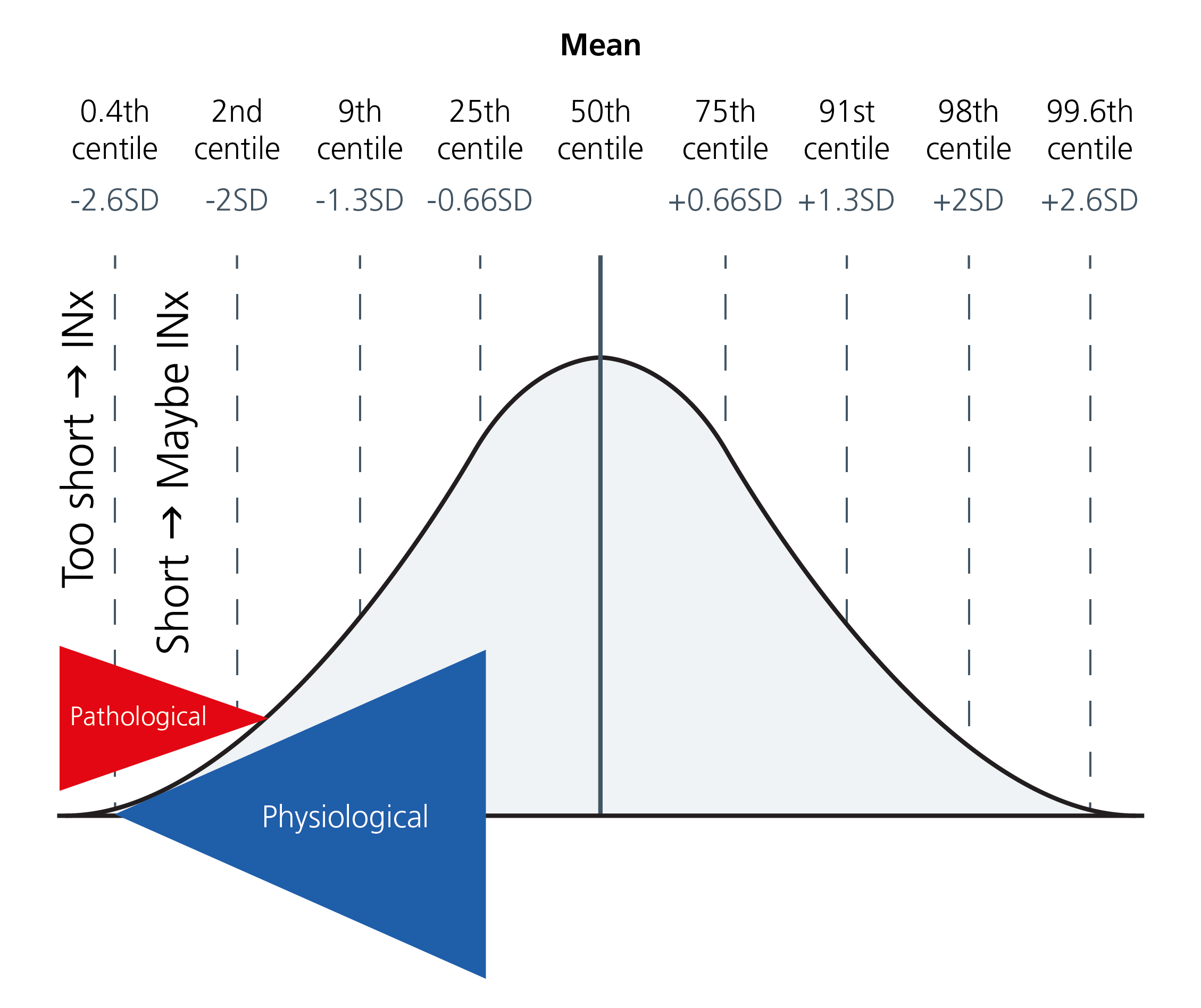

A key clue in identifying pathological causes of short stature is the degree of presentation. Physiological causes tend to cause mild short stature (for example, a height 2.01 standard deviations (SD) to 1.34SD below the mean (second to ninth centile)), whereas pathological causes tend to be severe with a height 2.01SD below the mean (below the second centile). Since familial causes make up the majority of cases, short stature must always be interpreted in the context of parental heights and mid-parental height centiles.

A pathological cause should be considered in scenarios including (but not limited to):

- a height (or length) under 2.68SD below the mean (below the 0.4th centile);

- a height that crosses (downward) two centile lines;

- a height between 2.68SD and 2.01SD below the mean (0.4th–2nd centile) that causes concern (because, for example, there is no alternative, obvious explanation, such as familial height or constitutional delay);

- other features suggestive of a genomic cause, such as:

- dysmorphism;

- multi-system involvement;

- disproportion of trunk, limbs (rhizomelia, mesomelia, acromelia) or head size;

- other bone development features or radiological changes (for example, epiphyseal, metaphyseal or diaphyseal changes), including:

- enlarged joints;

- slender bones;

- overgrowth;

- anomalous bone density (dense or osteopenic);

- presence of dislocations;

- fractures;

- bony lumps;

- stippling;

- striations;

- bowing;

- osteolysis;

- osteomyelitis;

- synostoses; or

- advanced or delayed ossification; and/or

- a family tree suggestive of a Mendelian inheritance pattern.

Severity of short stature as a clue

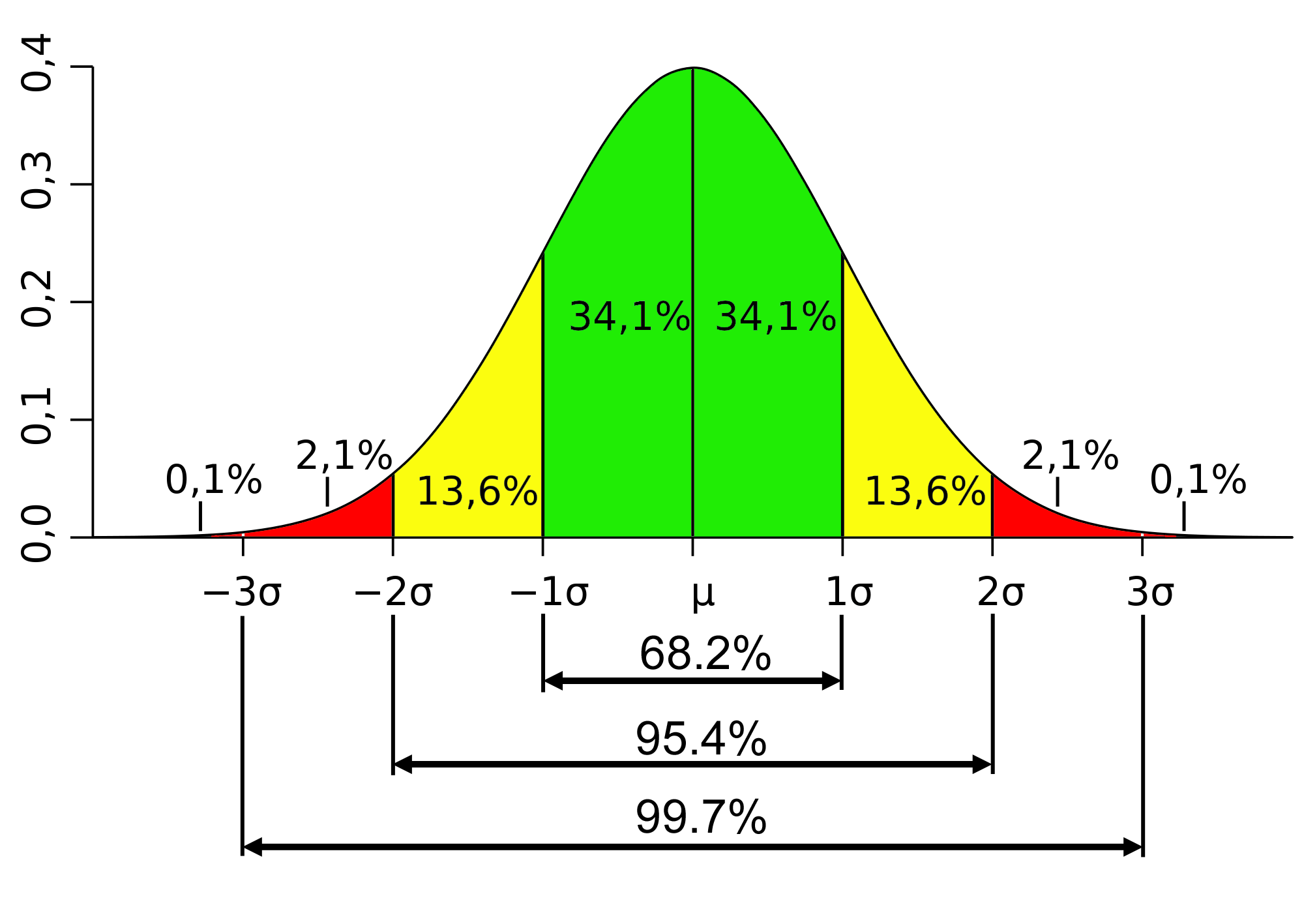

Figure 1: Standard bell curve distribution

This diagram has been included with kind permission from Dr Jody Muelaner.

Figure 1 shows a bell curve of normal distribution. The mean is represented by ‘μ’, and standard deviation by ‘σ’.

By definition, 95% of the population fall within 2SD above or below the mean.

In the context of height centile charts, the second centile roughly corresponds to 2SD below the mean. Therefore, anyone with a height below the second centile is outside the ‘normal’ range, but might still be part of normal variation.

In contrast, 3SD above or below the mean represents 99.7% of the population, and therefore any height of 3SD below the mean (approximately below the 0.4th centile) is unlikely to be part of normal variation. A height below the 0.4th centile is often pathological in cause and requires further investigation (INx) – see figure 2 below. The exception is prematurity.

Figure 2: Interpretation of the UK growth reference charts

This diagram has been included with kind permission from ClinicalGate.

Onset of short stature as a clue

Different factors contribute to a greater or lesser degree in determining growth, according to age. If short stature is identified prenatally, or presents in the early postnatal period (for example, in infancy), genetic causes are more likely.

The list below describes three stages of life and the most important corresponding factors for growth.

- Infancy: Nutrition, genetics.

- Childhood: Growth hormone, thyroid hormone.

- Puberty: Gonadal steroids, growth hormone, thyroid hormone.

Resources

For clinicians

- Skeletal Dysplasia Management Consortium: Best practice guidelines

- Skeletal Dysplasia Group (promotes teaching and research)

References:

- Firth HV, Hurst JA. ‘Oxford Desk Reference Clinical Genetics and Genomics. 2nd ed.’ Oxford University Press 2017: pages 158–159. DOI: 10.1093/med/9780199557509.001.0001

- Mortier GR, Cohn DH, Cormier‐Daire V and others. ‘Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2019 revision’. American Journal of Medical Genetics 2019: volume 179, issue 12, pages 2,393–2,419. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61366

- Spranger JW, Brill PW, Hall C and others. ‘Bone dysplasias: an atlas of genetic disorders of skeletal development’. Human Genetics 2019: volume 138, issue 7, page 787. DOI: 10.1007%2Fs00439-019-02038-0