Wilson disease

Wilson disease is a rare genetic disorder of copper metabolism, leading to excessive copper accumulation. Affected individuals can present with liver dysfunction, movement disorder and/or neuropsychiatric symptoms. The condition is treatable. Delays in diagnosis can lead to irreversible disability or death.

Overview

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by variants in the ATP7B gene. The ATP7B protein enables biliary excretion of copper and loading of copper onto caeruloplasmin. Patients typically present before the age of 40 with either hepatic (younger) or neurological (older) presentation. Children can present with behavioural changes. Hepatic presentation ranges from abnormal liver tests to acute liver failure. Diagnosis can be challenging, but timely treatment is important to remove excess copper, improve symptoms and avoid life-threatening complications.

Clinical features

Clinical features of Wilson disease are listed below.

Hepatic:

- abnormal liver function;

- jaundice;

- hepatic steatosis on imaging;

- cirrhosis; and/or

- acute liver failure.

Neurological:

- dysarthria;

- postural tremor;

- movement disorders (dystonia and/or chorea);

- parkinsonism;

- dysphagia;

- seizures;

- sleep disorders; and/or

- facial muscle spasm (risus sardonicus).

Psychiatric:

- depression and anxiety as both a symptom and response to living with a chronic disease;

- impairment of executive function, memory and cognition, which may be progressive;

- behavioural changes, including irritability or aggression; and/or

- psychosis (with paranoid delusions) in combination with symptoms listed above.

Other:

- haemolytic anaemia;

- renal tubular acidosis; and/or

- Kayser-Fleischer rings on slit-lamp examination.

For more information on biochemical and genomic testing and management, see the British Association for the Study of the Liver’s guidance. See also Presentation: Patient with copper overload.

Genomics

Wilson disease is a monogenic autosomal recessive condition caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous variants of the ATP7B gene on chromosome 13. More than 800 gene variants in ATP7B have been linked to the development of the disease, with common variants being represented in different populations across the world. This genetic diversity contributes to the spectrum of clinical presentation and disease severity.

Diagnosis

Wilson disease is diagnosed by specialist interpretation of clinical tests in the correct clinical context. Testing for the disease should be considered in:

- children and adults presenting with liver disease;

- children and adults between 5 and 50 years old presenting with progressive movement disorder; and

- children and adults with unexplained Coombs-negative haemolytic anaemia.

Tests to support the diagnosis of Wilson disease include:

- serum caeruloplasmin tests, where:

- very low serum-caeruloplasmin levels (<0.1g/L) are highly suggestive of Wilson disease;

- moderate-low levels (0.1–0.2g/L) can be caused by Wilson disease or other conditions including systemic inflammation; and

- normal levels of serum caeruloplasmin reduce the odds of Wilson disease;

- urinary 24h copper collection, where:

- elevated 24-hour urinary copper levels (>0.64μmol/24-hour) are supportive of Wilson disease;

- slit lamp examination, where:

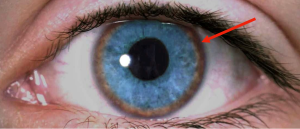

- Kayser-Fleischer rings (see figure 1) are copper deposits at the periphery of the cornea, highly suggestive of Wilson disease; slit lamp examination by an experienced ophthalmologist is often required; and

- ATP7B gene sequencing.

Other tests include:

- full blood count:

- thrombocytopaenia;

- microcytic anaemia with elevated reticulocyte count (suggesting haemolytic anaemia);

- liver function tests (all patterns of liver dysfunction possible), looking for:

- elevated bilirubin;

- elevated aminotransferases;

- elevated bilirubin:alkaline-phosphatase level;

- liver imaging for signs of cirrhosis/portal hypertension;

- magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (even in absence of neurological symptoms);

- liver biopsy with tissue copper quantification; and

- Leipzig scoring system (under specialist guidance).

For more information on testing, see the British Association for the Study of the Liver’s guidance.

Figure 1: The Kayser-Fleischer ring is demonstrated here as brown pigment (red arrow) at the periphery of the cornea.

Inheritance and genomic counselling

- Wilson disease is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder affecting 1 in 50,000 individuals in the UK.

- If both parents are carriers of the pathogenic variant, with each pregnancy there is a:

- 1 in 4 (25%) chance of a child inheriting both gene copies with the pathogenic variant and therefore being affected;

- 1 in 2 (50%) chance of a child inheriting one copy of the gene with the pathogenic variant and one normal copy, and therefore being a healthy carrier themselves; and

- 1 in 4 (25%) chance of a child inheriting both normal copies and being neither affected nor a carrier.

- The carrier frequency for pathogenic variants is 1 in 65 to 1 in 70, though it is common practice to screen the children of affected individuals. Siblings of affected individuals should also be offered screening for Wilson disease.

- Normal biochemical testing in an at-risk individual does not clearly differentiate between those at risk of future symptoms (asymptomatic individuals with biallelic pathogenic ATP7B variants) and those who are not at risk (heterozygous carriers or non-carriers).

Management

Individuals with Wilson disease should be managed in a specialist centre. The mainstay of treatment is lifelong copper chelation therapy to reduce excess copper levels. D-penicillamine is used as first-line chelation therapeutic in England, whereas trientine (dihydrochloride or tetrahydrochloride) is reserved for cases of D-penicillamine intolerance. Zinc salts should not be used first-line in symptomatic Wilson disease.

Management of Wilson disease depends on the urgency, severity and phenotype of presentation: acute liver failure is a medical emergency and urgent referral to liver transplant centre is indicated; additionally, neurological symptoms can worsen during initial chelation therapy and so chelation therapy needs to be carefully titrated, starting at a low dose.

Longer-term management includes: monitoring urinary copper levels, screening for secondary complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma in individuals with cirrhosis, and treatment of neurological and psychiatric symptoms requiring multidisciplinary working.

There are currently no approved gene therapies for Wilson disease.

Resources

For clinicians

- GeneReviews: Wilson’s disease

- OMIM: Wilson disease, WND

References:

- Shribman S, Marjot T, Sharif A and others. ‘Investigation and management of Wilson’s disease: a practical guide from the British Association for the Study of the Liver‘. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022: volume 7, issue 6, pages 560–575. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00004-8

For patients

- British Liver Trust: Wilson’s disease

- Wilson’s Disease Support Group – UK