Autosomal dominant inheritance

Autosomal dominant conditions are caused by variants in genes on one of the 22 autosomal chromosomes. The condition presents in the heterozygous state, where the pathogenic variant is present in only one copy of the gene.

What is an autosomal dominant condition?

Humans usually have two copies of each autosome, and therefore two copies of each gene. These copies are called alleles and they can be the same or different. With autosomal dominant conditions, features associated with the condition present when one copy of the gene has the pathogenic variant, while the other copy is usually unaltered.

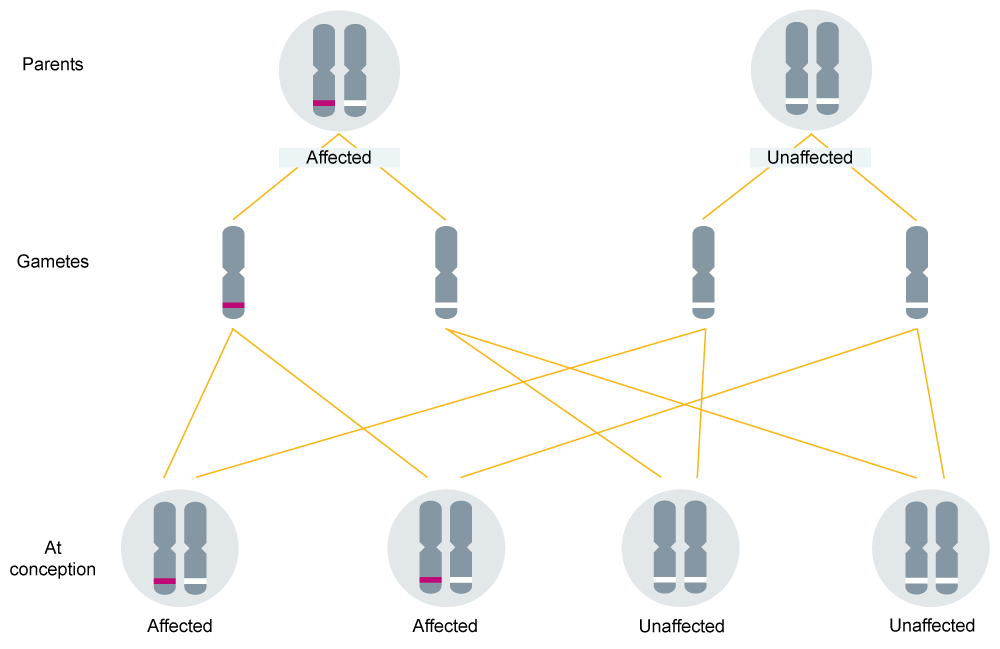

An affected individual has one non-pathogenic (or ‘wild type’) allele, and one variant allele (or ‘mutation’). They have a 1-in-2 (50%) chance of passing on the variant allele, and therefore the condition, to each of their children (see figure 1).

It is important to remember that chance has no memory, meaning that the 1-in-2 (50%) chance of inheriting the altered gene for the condition applies to each child, irrespective of whether or not the parents have already had children with, or without, the condition.

Figure 1: Autosomal dominant inheritance.

Watch this short animation to see the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern in action.

Features of an autosomal dominant condition in a family

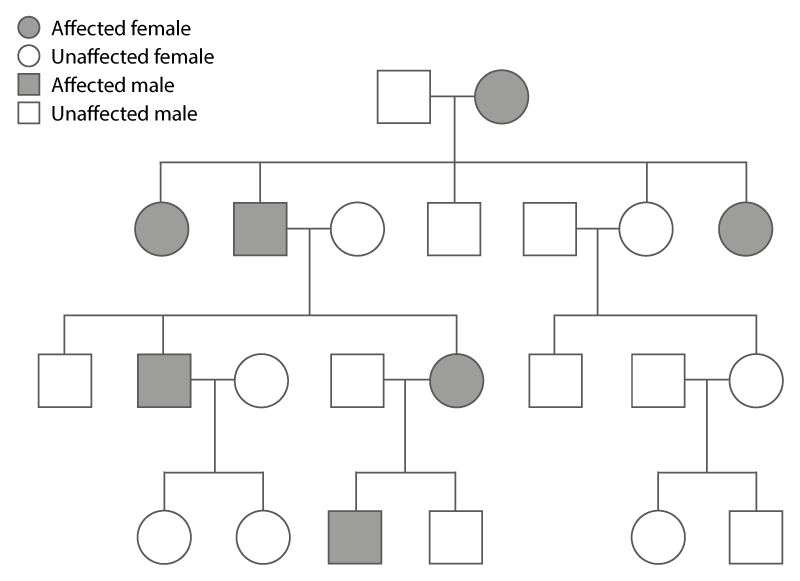

When looking at a patient’s family history, the presence of an autosomal dominant condition shows distinctive features, which can be identified by drawing a genetic family history (or pedigree) – see figure 2.

The main features of autosomal dominant inheritance include:

- males and females are affected in roughly equal proportions;

- individuals in more than one generation are affected if the condition is inherited. Sometimes, however, the condition can arise for the first time (de novo) in the affected individual; and

- affected males and females are both able to pass the condition to their sons and daughters.

Figure 2: Autosomal dominant inheritance within a family.

Note that autosomal dominant pedigree interpretation can be affected by confounding factors such as incomplete penetrance and the presence of phenocopies.

Incomplete penetrance occurs when not everyone who has the pathogenic variant manifests disease. An example of this would be hereditary breast and ovarian cancer caused by BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants. While the lifetime risk of cancer is increased by having one of these variants, not everyone with a pathogenic BRCA variant will develop cancer in their lifetime.

Presence of phenocopies is where individuals don’t have the pathogenic variant but nevertheless appear to have the condition. Again, a good example would be a pedigree from a family with a pathogenic BRCA variant, where an individual who doesn’t have the BRCA variant nevertheless develops breast cancer (which is, after all, a relatively common condition in the general population).

Clinical examples

There are many known autosomal dominant conditions and likely many more not yet described. The table below lists a few of the more common autosomal dominant conditions seen in UK clinics.

| Condition | Gene(s) | Salient features |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | PKD1, PKD2 | Fluid-filled cysts develop in the kidneys, with enlargement and progression to renal failure. Cysts may also develop in other organs, particularly the liver. Onset is usually in adulthood. |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | NF1 | Multiple café au lait pigmentations on the skin, and neurofibromas (benign tumours) growing in the skin and along nerves. Risk of pressure effects and malignant transformation. |

| Familial hypercholesterolaemia | LDLR, APOB, PCSK9 | Raised serum cholesterol leading to deposition in blood vessels, tendons and skin, and a high risk of early onset coronary artery disease. |

Key messages

- An autosomal dominant condition only requires one copy of a gene to be altered for the condition to present.

- The chance of a child inheriting the variant (and developing the condition) from an affected parent is 1-in-2 (50%).

- Incomplete penetrance can occur when not everyone who has the pathogenic variant develops the disease, for example in the case of someone with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant.

Resources

For clinicians

- NHS England’s Genomics Education Programme course: Genomics 101: Dominant, Recessive and Beyond

- NHS England: National Genomic Test Directory and eligibility criteria

For patients

- University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust: Dominant inheritance of genes