Your genome is unique. A copy is found in almost every cell in your body and is organised into 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs.

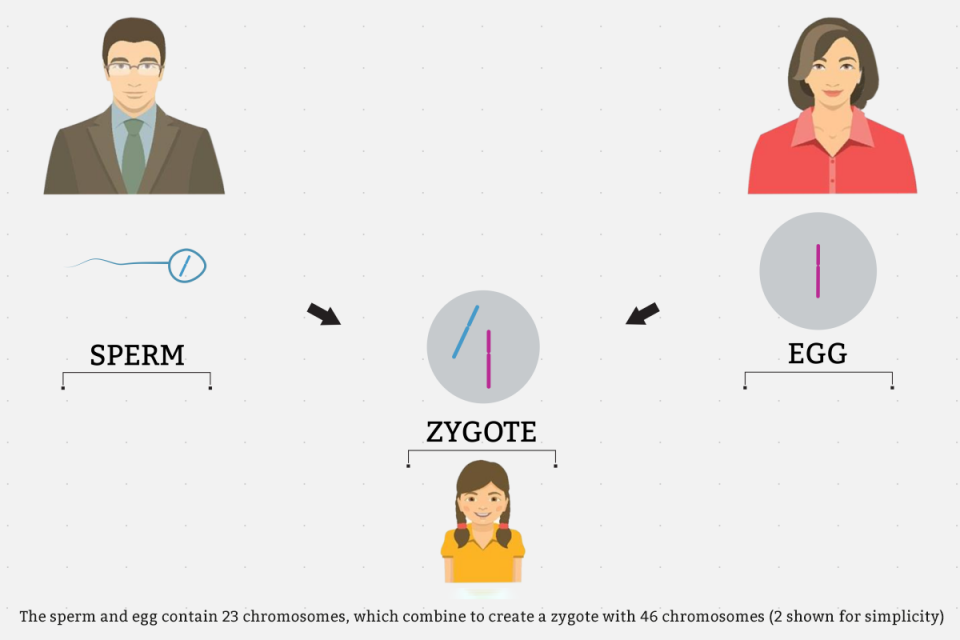

But where does your genome come from? To answer this, we must go back to the point of your conception, when your father’s sperm fused with your mother’s egg.

The sperm and egg are specialised cells called gametes and are unique in comparison to most of the other cells in the body, as they only contain half the usual number of chromosomes. At fertilisation, half of your father’s genome is mixed with half of your mother’s genome to form your complete genome.

So if our genomes come from our parents, why don’t all siblings look the same? This is because - unless you are an identical twin - the egg and sperm that created you contained different combinations of your parents' DNA than the egg and sperm that created your brother or sister.

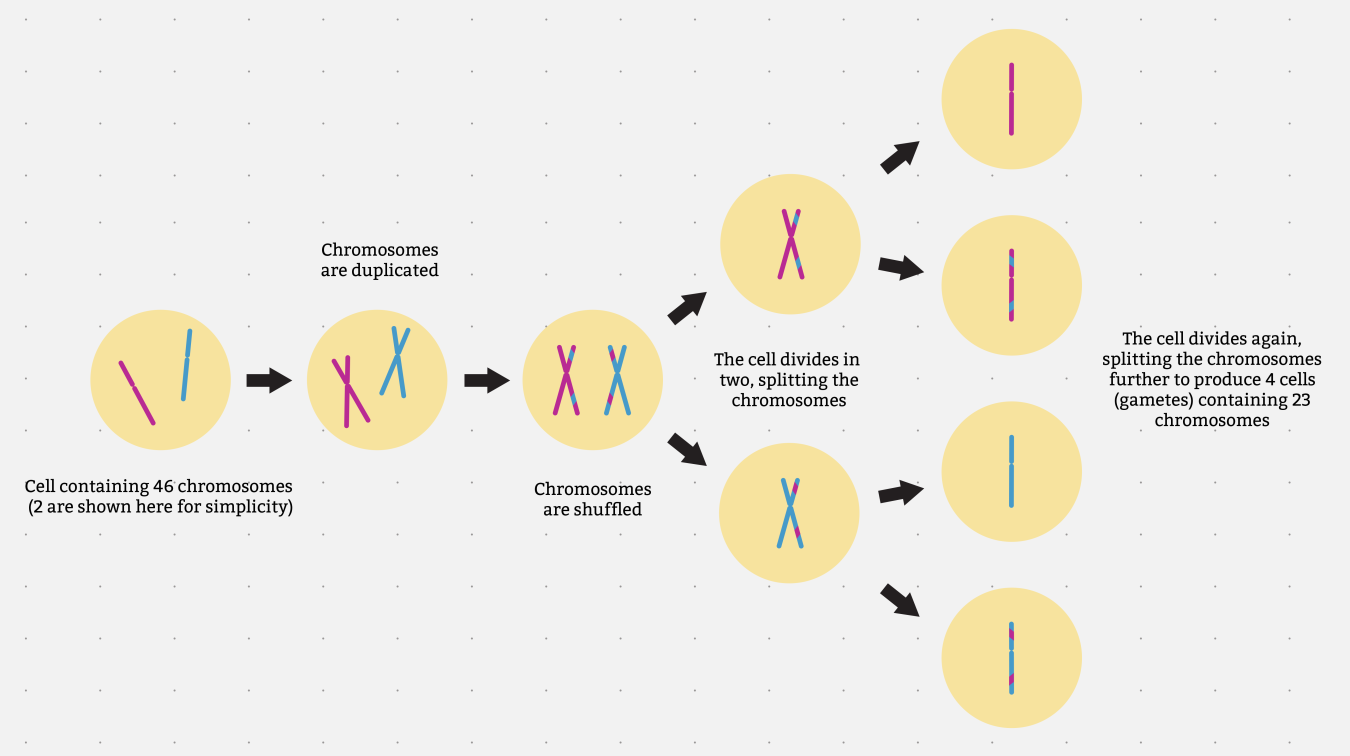

The different combinations are because of how gametes are formed, through a type of cell division called meiosis, where a cell containing 46 chromosomes divides to produce four cells, each containing 23 chromosomes. During meiosis, the chromosomes are duplicated, shuffled and separated, which ensures that each gamete produced is unique.

Meiosis: How gametes are formed

At fertilisation, a cell is formed called a zygote, which then undergoes another type of cell division called mitosis. This type of cell division differs from meiosis, as rather than producing four cells with half the number of chromosomes, it produces two completely identical cells.

The two cells, known as daughter cells, then divide to produce two new cells, which also divide and so on. Cells in our body undergo mitosis not only for our growth and development, but also to repair tissue or replace dead cells.

Watch the animation to see this process in action.

As the genome is passed from both parent to offspring and from cell to cell in our body, any change in the DNA - known as a variant - can also be passed on.

In healthcare, this becomes significant if the variant is associated with a particular medical condition. For instance, if a parent knows that there is a chance their child might inherit a condition, it could influence their reproductive choices or help them prepare for the care of their child. Equally, knowing that a variant cannot be inherited can be equally important to an individual.

Watch this film to hear Beskida Fejzullahu talk about her family's journey to discovering the genetic variant present in her son Arvin, and how they approached a subsequent pregnancy.

Do you want to learn more about genetic inheritance? Try one of our courses and resources, below!