In this teaching scenario, Jenny explains her ‘diagnostic odyssey’ and the challenges she faces living with two different inherited conditions: facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy and maturity onset diabetes of the young

A 49-year-old mother of three describes the challenge of living with two rare conditions, one inherited from each parent. Jenny also talks about the impact of the diagnoses for her children and the importance of being treated like a person rather than a problem.

Read Jenny’s story below and use the teaching moments and discussion points to design your teaching session.

AT-A-GLANCE

Clinical focus: Rare disease, common conditions

Nursing activities: Communication, identification, management, family care, testing, treatment

NMC platform and outcomes: 1 (1.8, 1.9, 1.11, 1.13, 1.14, 1.18); 2 (2.8, 2.9, 2.10); 3 (3.2, 3.3, 3.5, 3.11, 3.12, 3.15, 3.16); 4 (4.2, 4.3); 5 (5.4); 7 (7.1, 7.8)

Jenny’s story

Introducing Jenny

1 I am writing my story as a 49-year-old wife and mum of three children aged 26, 22 and 20. I have, as one consultant put it, the ‘double whammy’ of having inherited two genetic diseases – one from each parent. I inherited facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) from my mother’s side of the family, and a form of diabetes called maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) type 3 from my father’s side. Both of these conditions are dominantly inherited and were diagnosed within a few months of each other in 2005.

Diagnosis: FSHD

2 My FSHD developed gradually since childhood. My mother has a much milder form of the condition than I have. She went to her GP as one of her shoulders had dropped and she couldn’t keep her handbag on. After lots of tests and then genetic testing, she was diagnosed with FSHD. I had had increasing problems including fatigue and issues with arm movement, and one of my shoulders had become misshapen and rounded. I was working as a nurse, and my days off were spent worn out in bed – luckily, I was a senior sister and spent much of my shifts doing paperwork and talking to patients. I eventually gave up nursing as, although I could manage my job, there was nothing left in me for my family and running my home when my shift was over.

3 I have always had an inquisitive mind and kept up to date with medical matters out of interest. When my mother had her diagnosis of FSHD, I researched it on the internet and in my textbooks; I just knew it was what I had too.

4 When I realised I had FSHD, the pain was becoming quite a problem. We are very lucky in that we have an excellent GP. When I went to see him, he had researched FSHD, printed off information sheets and was ready for me. He took my history and examined me and said he thought I had FSHD as I had some classic signs and symptoms. He said that I didn’t need genetic testing as the diagnosis was clear. My diagnosis was later confirmed at a muscular dystrophy clinic by a consultant geneticist with a special interest in FSHD.

Diagnosis: MODY

5 I have grown up in a family where diabetes is rife. At one stage, 9 out of 11 living family members had it – some were diagnosed as type 1 and others as type 2. I cannot remember a time in my life when I did not expect to get it myself. I had gestational diabetes three times and was diagnosed with type 2 after some higher than normal blood test results in 2004, but managed with diet and exercise as treatment. Sadly, five months later, our then 16-year-old son, who was well in himself apart from being thirsty and having sugar in his urine, was diagnosed as type 1. No tests were carried out first – he was started on insulin immediately. We gave the consultant at the hospital a copy of our family tree, and explained I was type 2 and my father was type 1 and asked for genetic testing. We were told it was impossible for us to be different types and were denied further investigation. It was as if they had a plan of care for a teenager who presented with symptoms but wouldn’t deviate from it or think outside the box.

6 By now, our son was very ill. He had stopped attending college regularly, having driving lessons, playing sport or doing what most teenagers do. He had a blood test that showed it was unlikely that he had type 1 diabetes, but the consultant dismissed it and said it was just developing slowly. Many evenings were spent with our son semi-comatose on the floor and I regularly got up in the night to test his blood. He couldn’t be left alone and I got to the point that I thought he would die. The consultant dismissing the last blood test result was the final straw.

7 I spent time researching genetic forms of diabetes on the internet and discovered a team in Exeter who were researching MODY. I discussed my findings with my GP who agreed that it sounded like our son had it, but as he was under the care of the consultant, he couldn’t do anything about it. I phoned the team in Exeter, and they were sure from what I told them about our son that he had MODY too. As he was so ill, they advised taking him off insulin immediately (although they do stress that it is important for patients to not do this themselves – it is very rare to do so without waiting for the results of genetic testing) and told me what to watch for and what action to take. Within a day or two of stopping the insulin, we had our healthy teenager back.

8 I was given a phone number so I could call one of the team at Exeter for support and advice, and was told that I would know within a couple of days if our son was in fact type 1 or not. He, of course, was absolutely delighted to stop having injections.

9 They also wanted both my son and me to have genetic testing, and explained that all we had to do was to send blood samples. Our GP gave permission for the surgery to take the blood. In the meantime, however, our diabetes nurse specialist phoned me, and I told her all that I had found out about Exeter and that I had arranged for our son and myself to be genetically tested for MODY. She was very cross with me and said that I had put her in a difficult position. I told her that I really didn’t care – finding out what was wrong with my son and making him well again was all that mattered to me. The professor from Exeter also phoned the consultant and told him we were both likely to have MODY, that he had taken our son off insulin and wanted our blood samples as soon as possible.

10 Me and my son both tested positive for the MODY gene, and within 48 hours of stopping insulin, our son was back to his usual well and bouncy self. The consultant asked to see me after we had received the correct diagnosis, but I refused to go. He had made a big mistake and risked a teenager’s life because he wouldn’t listen to us. The diabetes nurse specialist rang a few times too. She was very apologetic and said lessons were being learned, and we only hope they were.

Implications for the family

11 Getting the diagnosis confirmed that I had passed on a disease to my son, which was quite hard to bear until a friend said to me “but you have given him so much more”. Those few words helped me enormously – I don’t see him as a diabetic, I see him as a 6’6″ happy young man with lots of friends who is following his chosen career, and who happens to have diabetes too. I feel the impact of genetic testing will be greater for him, as he will know he has the potential to pass the disease on to his own children and will have to think about that, whereas I did not know of the possibility.

12 After we received our positive diagnoses of MODY, the MODY specialist nurse came to see us at home to provide information and answer all our questions. She took blood from our daughter for genetic testing but wouldn’t take blood from our youngest son until he was 16. I feel this was wrong as it left him as the only member of the family wondering whether he had MODY. He wanted to be tested at the same time as his sister. In the end, it turned out that neither of them has the MODY gene.

13 I have never been referred to genetic or specialist services, nor offered counselling, but as I mentioned before, I can talk over anything with my GP. All the information my children have, apart from when the MODY nurse visited, is from me and from what I have learned – mainly from the internet. None of them want to be tested for FSHD, although one of them seems to be showing signs that he has inherited it too. The children say it is because there is no treatment available and a positive diagnosis could have a much more major effect on their lives than MODY would. It could prevent them from choosing particular careers or cause problems getting mortgages or insurances. They have seen me get more and more disabled and although no one can predict the course or severity of the disease in each individual, they don’t want to live with the fear that my degree of disability may happen to them. They are not endangering their health in any way by not being tested. Being tested for MODY was much more important. Although potentially life threatening, it has much less effect on daily life, but you do need diabetic care and maybe treatment. The thing about genetic testing is once you know the result, you can’t unknow it.

14 Receiving diagnoses has had great importance for both myself and my family. A lifelong question about why there has been so much diabetes in my father’s side of the family has been answered, and those of us who have diabetes are now receiving the correct treatment and have somewhere to turn to for specialist information. The diagnosis of FSHD, although not fantastic news, reassured me that there wasn’t something more seriously wrong with me, and confirmed my feelings that something wasn’t ‘right’ and that it wasn’t ‘normal’ to feel as I did. For my children, it does mean that they have decisions to make later about being tested for FSHD themselves and about having their own children and risking passing the condition on, but hopefully they will be offered the appropriate genetic counselling when the time comes.

Management

15 One problem I do find is that I am rarely treated as a whole person. The professionals tend to see me as a case of one disease or another, whereas the two diseases intertwine with one another. For example, for MODY, I am supposed to watch my carbohydrate intake and exercise to keep my blood sugar down, but the advice for FSHD is to eat plenty of carbs for energy and rest to preserve my muscles. The drug of choice to manage muscle spasms in FSHD has the side effect of raising blood sugar levels, which is bad for MODY. The speech therapist came to see me because of swallowing problems with FSHD and wanted to teach me how to eat biscuits and told me to put custard or sauces on everything and to eat things like puddings, all of which are unsuitable for a diabetic diet, and when I said that I did not and was not allowed to eat these foods, she could not adjust her information on swallowing to a diabetic diet. Patients with MODY are very prone to hypos (low blood sugar levels) but my painkillers for FSHD are quite strong and make me very sleepy. I feel I cannot take my diabetic medication when I need painkillers too, as I might develop a low blood sugar but be too ‘drugged’ to wake up and do anything about it, with disastrous consequences. It is a constant struggle balancing the needs of one disease against the other.

Final thoughts

16 If I could finish with a last note to any healthcare professionals who have read this, I would like to say that there are many changes and developments in medicine, and it would be very hard to keep up with them all. However, if you meet me or someone similar to me and haven’t heard of their diseases before, it is okay to say that they are new to you, and that you are going to have to go and ask someone for advice or Google them first. I would think much more of you and feel that you were giving me a higher standard of care than if you carried on treating me, pretending you knew all about my conditions, when it was obvious you hadn’t got a clue.

Educator touchpoints

Teaching moments

Paragraph 1 | Explore these conditions. What is the genetic cause and inheritance pattern for each of them?

Paragraph 2 | Both Jenny and her mother are diagnosed with FSHD but Jenny’s mother has a milder form. Explore the concept of penetrance.

Paragraph 5 | What is a family tree and why would this be helpful for Jenny’s diagnosis?

Paragraph 9 | What would be the type of genetic test used here?

Paragraph 10 | There is a not a MODY gene, but genes with a particular variant can cause the condition. There are many genes associated with the condition.

Paragraph 14 | What is a genetic counsellor? Explore this role.

Discussion points

Paragraph 4 | Consider the importance of recognising clinical clues and red flags when identifying individuals with genetic conditions.

Paragraph 5 | With diabetes running in the family, Jenny expected to get it. How could you support these feelings?

Paragraph 5 | Jenny was told it was impossible have a different type of diabetes than her father. How could this have been handled differently by the consultant?

Paragraph 7 | How could you support Jenny when faced with these conflicting opinions from her GP and consultant?

Paragraph 7 | Just because the condition is ‘in your DNA’ does not mean that it cannot be treated or managed.

Paragraph 9 | Discuss the nurse specialist’s behaviour. Why may she have reacted like this?

Paragraph 10 | What lessons do you think could have been learned from Jenny’s experience in getting a diagnosis?

Paragraph 11 | Discuss Jenny’s feelings of guilt. How could you support and reassure her?

Paragraph 11 | Discuss how the diagnosis may later impact on Jenny’s son’s choices to have a family of his own? Who could support him here?

Paragraph 12 | Do you think it is was the right decision not to test Jenny’s youngest child?

Paragraph 13 | Individuals may or may not want to know about a genetic diagnosis. Why could this be?

Paragraph 14 | Even though Jenny’s result was positive, what did she feel she gained from the diagnosis?

Paragraph 15 | Discuss some of the reasons Jenny is not seen ‘as a whole person’ when it comes to her conditions and why both conditions are treated separately.

Paragraph 15 | How could Jenny’s experience of how she is treated be improved so that both diseases are recognised?

Paragraph 16 | It is okay not to know everything. What are the dangers of giving answers rather than admitting that you are unsure?

Further learning

FOUNDATION KNOWLEDGE

A short animation to help explain dominant inheritance patterns

2 minutes

Learn the different ways that genetic conditions can be inherited within a family

30 minutes

Learn about how a genetic family history can help to identify an inherited condition

30 minutes

Tips and tools for communicating with patients about genomics

30 minutes

Practical tips and tools to help you read, take and draw a genetic family history

15 minutes

EXTENDED LEARNING

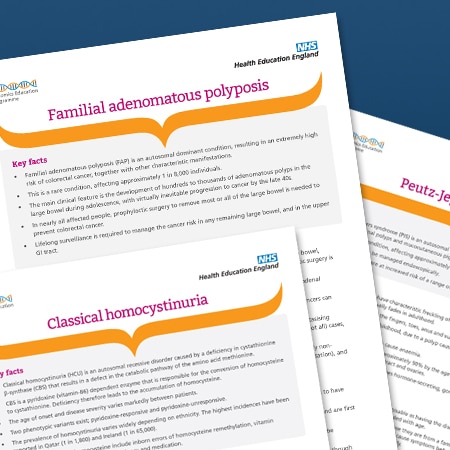

Key facts about the condition, including its clinical features and genetic basis

5 minutes