In this teaching scenario, a mother explains receiving a life-ending diagnosis for her seven-month-old daughter, Violet, and the emotional challenge of undertaking genetic testing to find the cause

A mother talks about the short life of her first child, Violet, who was admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit at seven months with a blood clot in her brain. She explains the family’s mixed experience of undergoing exome sequencing to find answers, from consent to receiving results.

Read Violet’s story below and use the teaching moments and discussion points to design your teaching session.

AT-A-GLANCE

Clinical focus: Rare disease

Nursing activities: Communication, family care

NMC platform and outcomes: 1 (1.2, 1.9, 1.11, 1.13, 1.14); 2 (2.8, 2.9); 3 (3.5, 3.6); 4 (4.2, 4.3); 5 (5.4); 7 (7.1)

Violet’s story

Introductory note

While exome and whole genome sequencing for critically ill children is available in the UK, looking for and reporting on secondary findings (not associated with the condition that testing was sought for) is not currently offered in the NHS. There is currently an evaluation taking place to understand whether these additional findings could be reported in the future. We have included this story in the toolkit as the scope of test described might be offered in the future.

This scenario is based on the following article, used with the permission of the author:

Robinson J. ‘Ask Me Later: Deciding to have clinical exome trio sequencing for my critically ill child‘. Genetics in Medicine 2021: 23, 1836-1837. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01231-9

Diagnosis

1 During my pregnancy, both my husband and I accessed genetic testing privately in the form of carrier screening and non-invasive prenatal testing due to my age and our infertility issues. A genetic counsellor had also spoken to us to talk over our family history, which, by all accounts of things, was normal. Even though we had this experience, none of it would prepare us for what was to come following the birth of our daughter.

2 Violet was born visibly healthy; she was our first child, and we were delighted. One day though, six months after her birth, she woke listless and lethargic, but had no fever. This persisted for a couple of days, but she seemed to be on the path to recovery. The next morning though, it was clear this was not the case. We took her to see our GP who told us to keep an eye on her and to call back if the symptoms continued. Four days later, we were rushing her to hospital. Her skin had become mottled, and she was running a fever. Her bright blue eyes had turned dark and unfocused. The clinicians diagnosed her with sepsis and after two days of fighting for her life she was transferred to the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) at the big university hospital in our city. The doctors told us she had a blood clot in her brain and her prognosis was unclear. Violet was unstable, with ongoing subclinical seizures, the infection impacting every system in her body. To this day we do not know what caused the infection.

Making decisions

3 So, it was seven months after her birth and here we were, sat in the PICU being told that Violet’s clot was life-ending. There were several medical teams looking after Violet and their care was amazing, but it was the haematology team who recommended sequencing her DNA. The clinicians told us that it was possible but not likely to change Violet’s treatment or her prognosis, but it may explain why she was so ill. Knowing the cause of our daughter’s condition might help my husband and I make some sense of this incredibly difficult situation or help others in the future. We both agreed.

4 A clinical geneticist came to see us in the unit and they asked us both about our familiarity with DNA sequencing. I told them I had some understanding of what this meant from my previous role as a research scientist. By saying this, I got the impression that the geneticist assumed I knew more than most. On saying this and with no comment from either of us, they left, leaving us with the consent documents. Looking back, I wished the geneticist would have given us the opportunity to ask more questions, more so for my husband’s sake. Or maybe a nurse could have followed up with us to see if we had any questions before we turned in the forms to give us more time to absorb the information considering everything else happening to us and our daughter.

Consenting

5 We were consenting to something called exome trio sequencing, which meant that both my DNA and my husband’s DNA would also be sequenced to see if either of us had changes in our DNA that we had passed on that might explain Violet’s condition.

6 My eyes glazed over as I read the consent papers. Some of the terminology was familiar, but there was so much to take in. For instance, buried in the documents were tick boxes around sharing our data to further research, receiving information about conditions that may be related to Violet’s current one and getting results not related to the condition, but that may be linked to others. In addition, we could also receive information on whether me or my husband had changes that could affect our own health. To be honest, none of this mattered, we wanted to make sure we had done everything we could at the time for our child. With the constant beeping of the PICU machines, my husband turned to me and asked ‘’what is this long list of genes I could get information on?”. I told him, as well as I could, that these genes are linked to conditions where treatment and management options are available, but from what I knew even a positive in one of genes didn’t mean you would definitely get the condition. I said I was going to check the box, but not the one on carrier status as we had gone through this process before Violet was born. My husband signed the document without saying a word.

7 When we handed the consent forms over, I noticed my husband had not checked a single box on the form. He’d written in large letters on the top of his form “Ask me later” and next to the empty check boxes “Ask me later, I cannot make these decisions under emotional duress”. No one picked up on this, I guess they assumed this just meant ‘no’ to return of results. I think, as any parent would, we wanted to do everything we could for our daughter during this time and all our attention was focused on that.

Dealing with information

8 The results came back three weeks later during Violet’s last week of life. They gave us some information. As well as reporting on Violet’s DNA, because we had opted for trio sequencing, her report would also show if a change had come from my husband or me. Nothing significant was found. I was interested though in a change of unknown significance that she shared with one of us. It also made me wonder if my husband had opted to learn more, the test may have picked up something that we could have done something about. Or whether this change could mean anything or not, and what it meant about our chances to have another child in the future with the same problems that Violet had. When we were ready to handle that type of information, could we find out?

Educator touchpoints

Teaching moments

Paragraph 1 | What is non-invasive prenatal testing?

Paragraph 1 | What is a genetic counsellor?

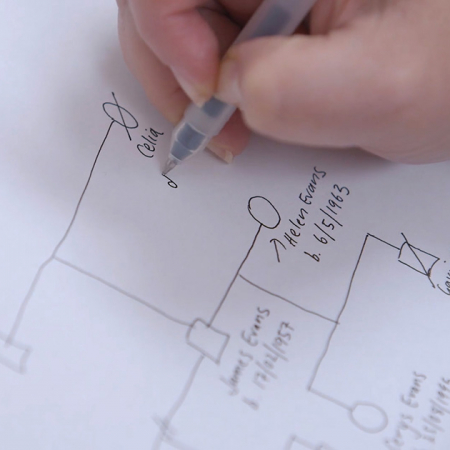

Paragraph 1 | What is a family tree in the context of genomics?

Paragraph 3 | What is DNA sequencing?

Paragraph 4 | What is a clinical geneticist?

Paragraph 5 | What is the exome? How does exome sequencing differ from whole genome sequencing?

Paragraph 8 | What is meant by a change of unknown significance?

Discussion points

Paragraph 1 | Why might age and infertility issues lead the family to have early investigations?

Paragraph 3 | Even though sequencing may not provide an answer, why might be knowing this still be helpful to the parents?

Paragraph 4 | What else could the clinical geneticist or other healthcare professional have done to inform the parents further on the test?

Paragraph 6 | What support could be offered to those making decisions in highly emotive situations?

Paragraph 6 | Does having a genetic change linked to a condition mean you will definitely get the condition?

Paragraph 7 | Do you think extra support should have been provided for the parents? What could have been done?

Paragraph 8 | What further support could be given to the family in the future? Who could they speak to?

Further learning

FOUNDATION KNOWLEDGE

Explore the different ways the genome can be investigated and how this is used in healthcare

30 minutes

Learn the different ways that genetic conditions can be inherited within a family

30 minutes

Tips and tools for communicating with patients about genomics

30 minutes

Find out the role genomics can play before a baby is born in this blog article

15 minutes

Explore the work of a clinical geneticist and gain an insight into the evolving challenges of the role

3 minutes

Explore the role genetic counsellors play in supporting patients through their genomic journey

4 minutes